Since the 1950s, American schools have been engaging in safety preparedness,

beginning with fire drills, evolving into additional emergency protocols, and

finally with active shooter training. Unfortunately, no evidence exists that these

measures bring any improvements in the sense of safety. As Dr. Daniel Siegel (2015) explains, students need to be “seen, safe, and soothed, in order to feel secure” (p. 145),

and these needs will not be met by current school safety practices alone. As

collective wisdom considers the emotional and social impact of these safety

measures, it is important to note that for more than a decade, US students have

been reporting how many of them miss school because of safety concerns. Karyn

Purvis and her colleagues remind us, there is a difference between being safe

and feeling safe: “Felt safety, which has to be determined by each

individual, includes emotional, physical, and relational security” (From The Connected

Child). It may be time to reconsider what is meant by

school safety and to determine what our children and young people really need

in order to feel the sense of safety required to thrive in school and beyond.

School Safety: A Perennial Issue for Some

Since 1999, the Center for Disease Control's Division of

Adolescence and School Health (CDC/DASH) has surveyed over four million US high

school students on health behaviors that contribute to physical, social, and

emotional problems. One of the questions addresses students’ sense of safety: “During

the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school because you felt

you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school?” From

2007-2017,

5-7% of US high school students have reported not going to school because of

safety concerns. These troubling results have remained stable with no

statistical difference across a decade.

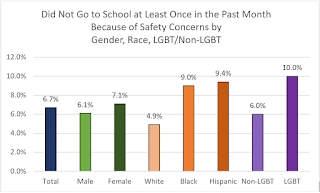

Looking deeper into the 2017 results, females have significantly

more safety concerns than males, and Black and Latino students have more safety

concerns than white students. Additionally, LGBTQ+ students have significantly

higher safety concerns than non-LGBTQ+ students. In a classroom of 30, two students stay home

at least one day a month because they are afraid before, during, or after

school.

The Neurobiology of Feeling Safe

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is often

held up as a framework for acknowledging both physiological and psychological

needs in schools, especially with regard to safety. The premise is that basic human

needs must be fulfilled before social, esteem, and self-actualization needs are

considered. At the base of human needs are physiological needs, such as food and

shelter. The next level of needs is focused on safety and security. This need

for safety can be met with limits, consistencies, routines, and predictability.

From there, efforts can be made to fulfill the needs for self-esteem and

self-actualization. Using this model, schools might easily simplify the safety needs

of their students and mobilize all adults in the schools to play pivotal roles

in meeting these needs.

However, as Patricia

Rutledge

and others note, this understanding is too simplistic, because it fails to take

into account the prerequisite for social connections at every level of the

hierarchy. While it may not be included in current discussions, Maslow’s

original model sets preconditions that do indeed recognize the social

environment. The freedoms to speak and to defend one’s self are noted as

preconditions, as are honesty, justice, and order in groups. Maslow (1943) asserts,

“These conditions are defended because without them the basic satisfactions are

quite impossible, or at least, very severely endangered” (p.384). According to Maslow, then, a healthy social

environment is an imperative for meeting individual needs, including safety

needs.

Considering the impact of the environment on individuals, Steven Porges

(2017) explains

feeling safe as a neurobiology in his Polyvagal Theory. The neurobiological responses to relationships

and to the environment determine whether humans feel safe, and these

instinctual responses take precedence over a cognitive determination of safety.

Porges challenges the traditional structural ideas of safety that focus on

physical measures as they may have no impact on the feeling of safety. In other

words, the environment determines whether or not people feel safe, and feeling

safe may not be based on logic or fact. Porges advocates a shift in thinking

about safety that is a simple thought: it matters how people treat one another.

The Polyvagal Theory also asserts that feeling safe is the natural

state of the brain. In this state, humans are connected and fully present. Because

the brain perceives no risk, it is open to new learning. “Safe states are not

only a prerequisite for social behavior, but also for accessing the higher

brain structures that enable humans to be creative and generative” (Porges,

2017, p. 50). This theory suggests that all learning, academic and social-emotional,

must happen in a perceived safe environment. As a by-product, then, in tending

to the neurobiology of feeling safe, student achievement is likely to increase,

as evidenced by several researchers who have seen the relationship between

strong school communities that prioritize social-emotional learning with increases

in student achievement (See the Collaborative

for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2019; Hagelskamp,

Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2013, among others).

A Sense of Safety First

Rather than considering security measures and drills alone, improving

school safety should focus on increasing the sense of safety, which

happens within a healthy school environment. While physical safety measures are

an important part of all safety plans, students feeling safe at school

is not the same as an adult declaration that a school is safe. When students feel safe at school, they are

more willing to engage in prosocial behaviors and their brains are ready to

take in new information, be it academic content or social-emotional learning. Most

importantly, when the focus is on students’ feelings of safety, it is possible

to reduce the concerning numbers of students, especially Black, Hispanic, and

LGBTQ+ students, who miss at least one school day every month because of safety

concerns.

References

Collaborative for

Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2019). Research: SEL Impact.

Retrieved from https://casel.org/impact/.

Center for

Disease Control (2017). Youth Risk Behavior Survey: data and trends report

2007-2017. Retrieved from Washington, DC:

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf.

Hagelskamp, C.,

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2013). Improving classroom

quality with the RULER approach to social and emotional learning: Proximal and

distal outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(3-4),

530-543.

Maslow, A. H.

(1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

National Center

for Education Statistics. (2016). Percentage of students ages 12-18 who

reported being bullied at school during the school year, by type of bullying

and selected student and school characteristics: Selected years, 2005 through

2015. In Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, School Crime

Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey (Ed.), Digest

of Education Statistics (August 2016 ed.). Washington, DC: NCES.

Porges, S. W.

(2017). The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative

Power of Feeling Safe. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Power of Feeling Safe. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Purvis, K. B.,

Cross, D. R. & Sunshine, W. L. (2007). The Connected Child: Bring hope and

healing to your adoptive family. In. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Rutledge, P.

(2011). Social Networks: What Maslow Missed. Retrieved from

http://mprcenter.org/blog/2011/11/social-networks-what-maslow-misses/

Siegel, D. J.

(2015). Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. New York:

Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

Julie E. McDaniel-Muldoon, PhD

·

Social Media Director, International Bullying

Prevention Association (www.ibpaworld.org)

·

Student Safety and Well-Being Consultant,

Oakland Schools (Waterford, Michigan)

·

Advanced Trauma Practitioner and Trainer, Starr

Commonwealth (www.starr.org)

·

More information:

o Email: jemmuldoon@gmail.com

o Blog: https://jemmuldoon.blogspot.com/

o Twitter:

@jemmuldoon

Women somatic therapist I would like to say that this blog really convinced me to do it! Thanks, very good post.

ReplyDelete